Quotes from a life

“Paintings are there to be experienced, they are events. They are also to be meditated on and to be enjoyed by the senses; to be felt through the eye.”

John Hoyland, 1979

Paintings are there to be experienced, they are events. They are also to be meditated on and to be enjoyed by the senses; to be felt through the eye.

The way that they are perceived, as with nature, will be conditioned by the individual onlooker’s feelings, background and temperament. Paintings are not intellectual, they don’t describe events, don’t tell a story, they are not concerned with history, literature, science, theatre, mathematics, or movement; they are still.

One discovers a painting as one might discover a forest with snow falling, and then suddenly, unexpectedly, come upon an open glade with sunlight penetrating the falling snow, simultaneously.

Paintings are not to be reasoned with, they are not to be understood, they are to be recognized. They are an equivalent to nature, not an illustration of it; their test is in the depth of the artist’s imagination.

7.8.78 (statement for Hoyland’s retrospective at the Serpentine in 1979)

“Painting should be a seismograph of the person”

Mel Gooding recounts the following in his 2006 book on Hoyland:

Following New London Situation (1961), at which the two paintings he had entered were sold respectively to the important father and son collectors, Alan and Ted Power, Hoyland was to go through a testing period, working without certainty of direction, trying to find a style that would give truer expression to his intentions than the formalist, optical ‘hard-edge’ works of 1961-62. Denis Bowen, the painter-critic, had referred to these paintings, in a complimentary way, as ‘exquisite and refined’; Hoyland remembers, ‘…when I read the word “exquisite”, I thought, well, if they’re exquisite, they’re not me. And I thought I want to be true to … my own character … painting should be a seismograph of the person and if I’m being exquisite then I’m being false. And that is why I ditched all that “exquisite” optical, hard-edged painting.

Gooding, M., ‘John Hoyland’, Thames & Hudson 2006, pp38-9

© John Hoyland, Mel Gooding and Cameron & Hollis, 2006

“Painting is the will and the whole self in harmony, without self-deception”

Artists live in the real world, but most of the time they are invisible. Occasionally they are wheeled out like performing bears, hence this occasion. We all live in a world of information, surrounded by a remorseless torrent of rubbish being poured daily into our minds. The dreariness of calculated processes, bad manners, dishonesty and no respect for the old or young. Lack of leadership in government and the church, the banks, the city, the media, style gurus, Spin Doctors, soundbites, public relations men, advertising, fashion and greed […] looking for the main chance under the guise of education, and the torch bearers of hype, the music and film industry, the men who sold their souls and have carried the young, ignorant and most vulnerable, in their hideous wake. Ethics and business are uncomfortable bedfellows. This is life in Britain.

As you will see, the only sanctuary left for the artist, or anyone else for that matter, is to escape into the imagination – in my case, through art.

Art is about making ethical and poetical judgements and developing discerning taste (and by this I don’t mean ‘good taste’), in order to bring together a number of generalities to a concrete formal conclusion, which the artist hopes will make a bridge between him and his audience. Art is about making transformations. This is done through the constant practice of producing art, but it is often the unexpected encounters and intuitive, irrational choices made along the way that bring about the transformation of work. There is also a selective body of knowledge, a context for art, of whatever form. Birthright, one’s culture, one’s genes, emotional make-up, being working class, middle class or aristocratic etc etc. Education, life’s accidents and the light of experience. There is also desire made concrete. Painting is the will and the whole self in harmony, without self-deception, but as Braque said, in the end the problem with art is that you can explain almost anything except the bit that matters.

I approach my work in a vaguely dialectical way through a form of criticism, trying to investigate a mixture of logic, imagination and empirical accident, trying to break the logical mould.

Over-valued reason is like political absolutism. Reason sets boundaries, wishing us only to accept the known and live in a framework as if we were sure how far life can extend. The more critical reason dominates, the more we are impoverished. Spontaneity is less about the unconscious and more about inventing new forms, new structures, in which hopefully can be embedded the spirit concealed within the image.

I would like to make archetypal images of wholeness and have tried to broaden my work over the years, to stretch abstraction, giving it a human face, incorporating the radiance of Matisse and Rothko, the plastic construction of de Staël and Hofmann, and the evocation and innovation of Miró and Picasso – and I’m the first to admit it’s a tall order. Picasso saw and learned from African art the freedom to distort, together with formal vitality. Jung said, ‘vivid colours attract the unconscious’ and Matisse spoke of ‘the beneficent radiation of colour and its power to heal’.

Unfortunately, we are hemmed in by kitsch and novelty, instant gratification and glib posturing, silly nostalgic homages to neo-data, manic conceits and self-aggrandisement, not to mention sexual politics. It is difficult for art to exist in such a low context – survival is threatened.

Britain is visually uncultivated, cultivation being fine as long as you stick to gardening and you’d better keep it neat. I want an art that has a spiritual dimension, but spirituality or the metaphysical cannot be built to order. We live in a secular, mass culture surrounded by cliché-ridden so-called advanced art that has become decadent and entirely commercial. Making art for art’s sake is the only way that honesty can be achieved. Finding the images that lie behind emotions produced by the mind, hand, eye, memory and heart.

London – and perhaps the whole of England – for me seems to have little or no poetry. It doesn’t encourage a poetic vision of life. Perhaps it’s the weather, the light, the vegetation and certainly many of the people.

Sometimes I hate my anglo-saxonness, the clodhopping, dull mongrelness. Perhaps this is my way to cling to other cultures for sustenance – the exotic in art, place, people and music. I never believed in the dominance of European culture. I want more magic, more drama, black or white but not grey. Not accountants, bank managers, computer programmers, trade unionists, hairdressers and media personalities. I feel swamped by the saturation techniques of the advertising men who more and more have taken over from the artist, the poet and the madman. England is a small, bland, mean little island with manufactured eccentrics, counterfeit emotions and anger – a controlled response as dead as a video. I want the spiritual and the sub-conscious blended with the external world. I have also wanted for a long time to make art that would communicate directly across racial, social, political and linguistic barriers and to pursue an open discussion with art, both old and new, in a diverse cultural context. Here one has to consider whether one’s own culture contains the models one needs in order to create new hybrids, because that is what it’s all about. Many artists in the past have been indebted to non-European cultural models and in the 21st century it would seem to be logical that this could occur. Otherwise, we shall drown in a sea of mediocrity.

From a talk first given at the Tate Gallery in 1994; and again in 2005 in Mauritius (titled ‘Invisible Artist or Performing Bear’)

“There is no place for cynicism, only joy, passion and wonderment, clarity and eagerness.”

Paintings are a seduction, one develops a relationship with these inanimate objects which becomes a bond like a living person, a mirror, a realm of elusive power. Art plays a game of structural truthfulness, it becomes alive. It contains and understands ecstasy through colour as light. The artist must try to make every song sing and push beyond the fixing of appearances. There is no place for cynicism, only joy, passion and wonderment, clarity and eagerness. Painting should be made to look easy, painting as the embodiment of what it is to be human. Paintings are a kind of dream language, and like music they propose a new reality. Simplicity can give them their greatest power.

From a talk first given at the Tate Gallery in 1994; and again in 2005 in Mauritius (titled ‘Invisible Artist or Performing Bear’)

“I don’t claim to be an intellectual but most artists don’t think enough.”

I don’t claim to be an intellectual but most artists don’t think enough. Artists who claim to think only think. And their thoughts are mainly trivial. Painting is a craft which may at times become art but real art is a rare commodity. But it is certainly the product of thought.

John Hoyland, June [?] 1998 (excerpt from notebook)

“Finally, you don’t give a f**k about anything, you just want to howl at the moon.”

When one is young and has experienced a good deal of rejection, you want to show everyone how tough you are. Later you want to show how clever you are. Later still, you want to see how far you can push yourself. And finally, you don’t give a f**k about anything, you just want to howl at the moon.

John Hoyland, 2006 (sketchbook entry dated 2.04.06)

“I can’t think of anything worse than just taking painting towards refinement”

I think painting should express all kinds of different things, not be limited. I can’t think of anything worse than just taking painting towards refinement, if you don’t allow yourself to change. I don’t force change on myself, it just happens. I’d probably get bored if I did the same thing all the time. Not so long ago I said I’d like to be able to paint anything in a painting. I think I’m getting there slowly. Robert Motherwell gave me a book on Miró. He’s supposed to be the great surrealist with a fantastic imagination but he went on the beach every day picking stuff up – a bit of string, a shell, a bit of wood. If Miró needed outside stimulation then who am I to think that I can keep on developing through a kind of formalist grid? That opened me up to plundering nature.

John Hoyland (Lambirth, A., The Spectator, May 2008)

“Paint can be physical, sensual, visceral or a puff of smoke. It can capture every human emotion.”

1. Paint is a magical substance, alchemic.

2. Paintedness, the difference between Frans Hals and Rembrandt (the bit that matters)

3. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes and don’t ever try to be a smart ass*. The art world is full of them.

* Stock-brokers, politicians and sales men are smart ass, not artists.

4. The more mistakes you make now the more you clear the way to find your own resolutions later.

Paint can be physical, sensual, visceral or a puff of smoke. It can capture every human emotion. It is infinitely variable in its manifestations.

To me video is dead. Video is television.

Advice to students, date unknown

“Art is craft, but sometimes it miraculously crosses over into Art.”

Sir,

There was once a student on the BA course at Chelsea School of Art – it was 1968 or 1969. He owned a beautifully polished, magnificent Harley Davidson motorcycle. It was a beautiful sight. He then offered it as his degree work; we failed him. In the present climate of Establishment thinking, he might well be showing it at the Tate Modern or the Venice Biennale; after all, it was a wonderful object – and he had spotted it. (These old arguments make me feel so ancient.)

Art is craft, but sometimes it miraculously crosses over into Art. Frans Hals was a wonderful painter, but he wasn’t Rembrandt and we don’t know why.

By merely painting an idea, or having an idea painted, the central act of creativity is removed; that is, the things that one discovers in the physical process of making the work, together with the intuitive decisions made along the way, and, of course, a bit of luck.

John Hoyland, RA Letter to the Editor, TLS, June 22, 2001

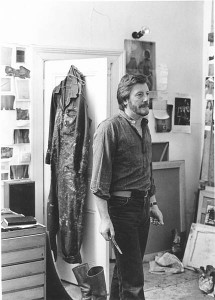

Still from 1979 BBC film ‘Six Days in September’ (Photo © BBC)